Minimal Basics of CUDA Programming

· 30 min read

GPUs are fast because of parallelism. The NVIDIA RTX 4090 has 16,384 CUDA cores (smaller, specialized compute units) compared to a high-end CPU's 16 to 24 general-purpose cores. Each GPU core is individually slower than a CPU core, but 16,384 of them running at once more than makes up for it.

CUDA is a C++ extension for writing programs that run on the GPU. You split a workload into small pieces, and each piece runs on a separate core in parallel.

PyTorch and JAX hide most of this from you. You allocate tensors, call tensor.cuda() or tensor.to(device), and the framework launches CUDA kernels behind the scenes. Under the hood, they call into CUDA libraries like cuBLAS for matrix multiplication and cuDNN for deep learning primitives.

For instance, performing vector addition in PyTorch is as simple as:

import torch

# Create two large vectors on the GPU

a = torch.rand(1000000, device='cuda')

b = torch.rand(1000000, device='cuda')

# Add them elementwise

c = a + b

This launches a GPU kernel—a function that runs on the GPU—adding corresponding elements of a and b in parallel. PyTorch handles the GPU memory management and thread launching for you.

But if you need to squeeze out more performance for a specialized workload, you'll want to understand what's happening underneath.

Quiz

Consider comparing CPUs to databases and GPUs to MapReduce workers, which operation would theoretically perform WORSE on a GPU compared to a CPU?

CUDA Kernels and Threading Model

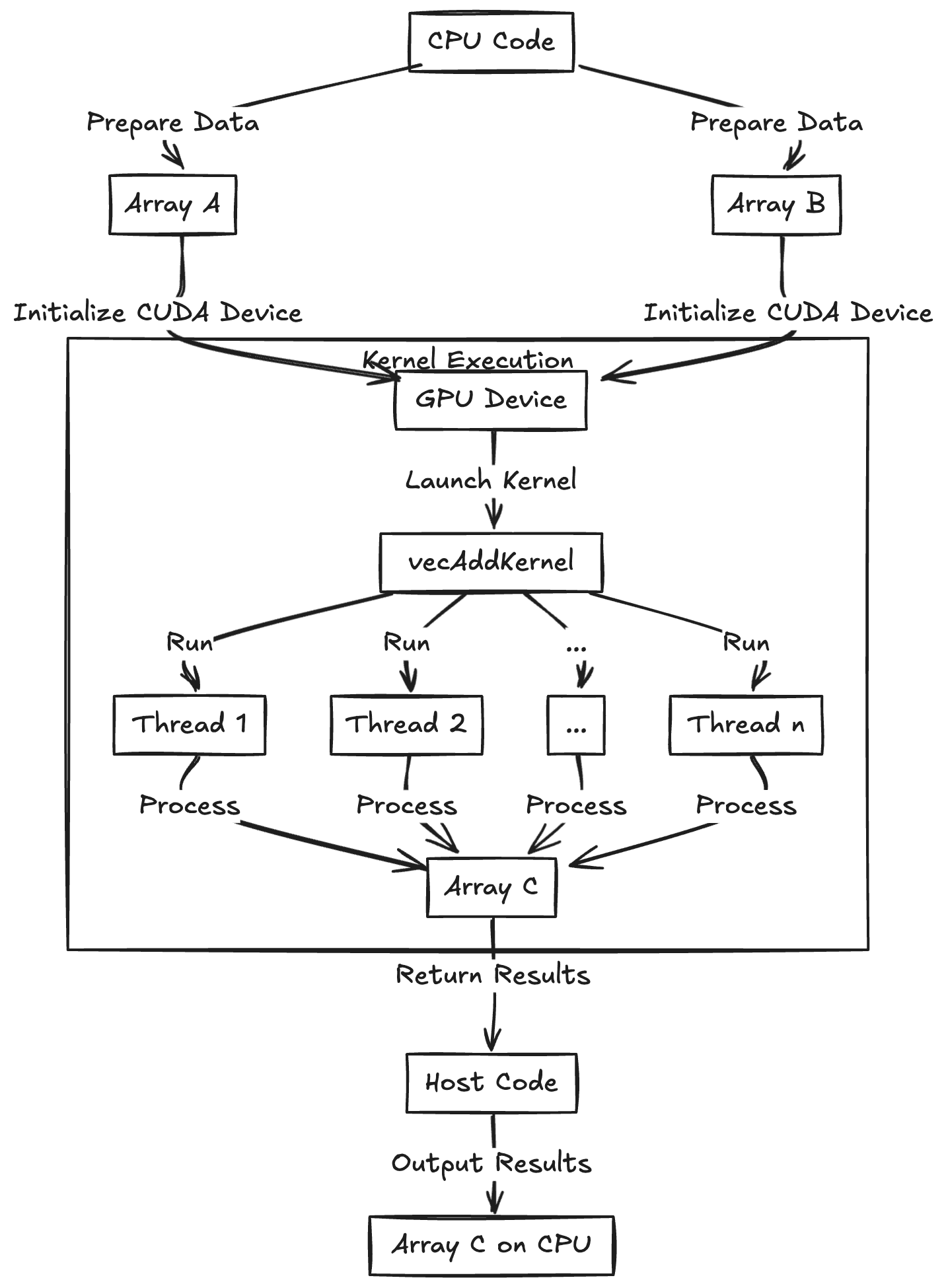

A kernel is a function that runs on the GPU. A kernel launch creates hundreds or thousands of parallel threads that execute that function simultaneously on different data. This is called the Single-Instruction Multiple-Thread model (SIMT): one program, many data pieces.

To add two arrays of numbers (A and B) and produce an output array (C), this is the CUDA C++ kernel function:

__global__ void vecAddKernel(float *A, float *B, float *C, int n) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

C[idx] = A[idx] + B[idx];

}

}

This code gives each thread a unique index idx into the arrays. The kernel uses each thread's index to have that thread add one element from A and B. The __global__ qualifier means this function is a CUDA kernel that runs on the device (GPU) and can be launched from host (CPU) code. The if (idx < n) guard is there because we can launch slightly more threads than the array length, and those extra threads simply do nothing if their index is out of range.

Kernel execution begins in the main CPU program (the "host code"), which configures how many threads to run. The kernel itself runs on the GPU, but host code is needed to configure and launch it. For example:

int N = 1000000;

int threadsPerBlock = 256;

int numberOfBlocks = (N + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

vecAddKernel<<< numberOfBlocks, threadsPerBlock >>>(d_A, d_B, d_C, N); // Launch configuration

This CPU code configures and starts the GPU kernel, specifying that we want numberOfBlocks * threadsPerBlock total threads, arranged as numberOfBlocks blocks of threadsPerBlock threads each.

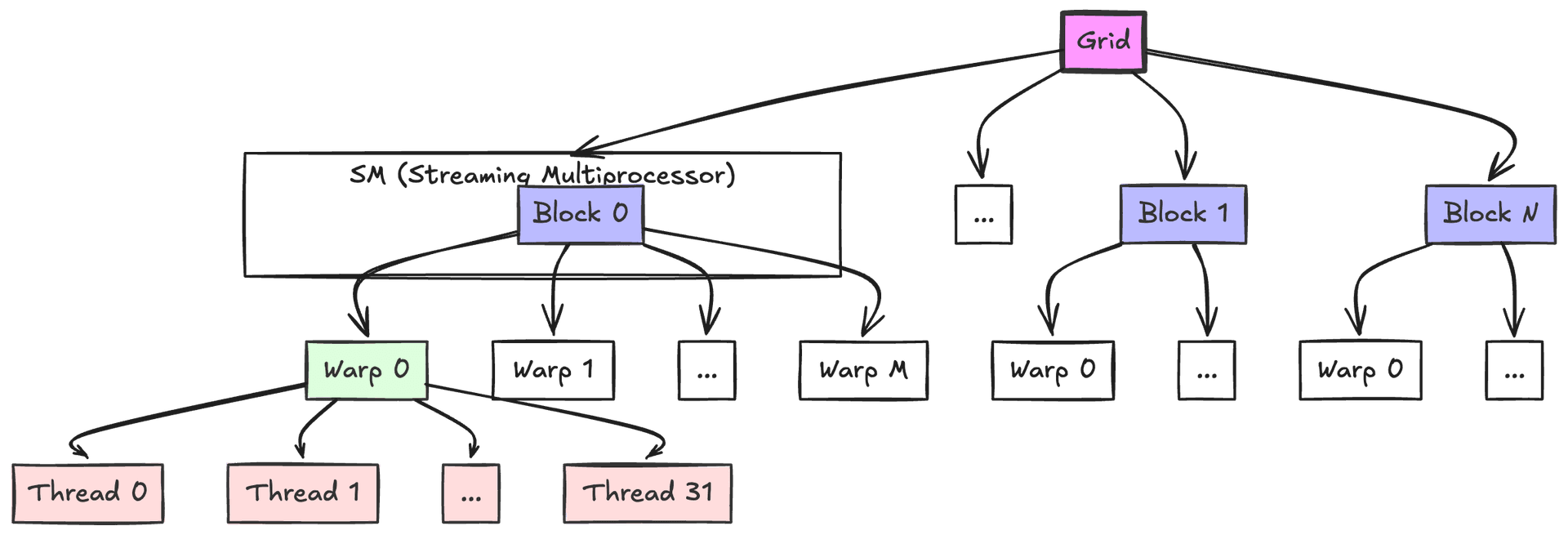

CUDA organizes threads into warps (groups of 32 threads that execute together), which are further grouped into blocks. Each block runs on a Streaming Multiprocessor (SM), which has limited resources like registers and shared memory. The block size affects how these resources are allocated and how many warps can run concurrently (a concept known as occupancy).

When threads in a warp hit an if-statement and some take one path while others take another, execution serializes. The hardware uses mask bits to track which threads should run each path—correct, but slower. Here's an example of warp divergence:

__global__ void divergentKernel(float *data, int n) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

// This condition causes warp divergence because threads within

// the same warp may take different paths

if (data[idx] > 0.5f) {

data[idx] *= 2.0f; // Some threads do this

} else {

data[idx] += 1.0f; // While others do this

}

}

}

// Launch configuration considering SM resources

int maxThreadsPerSM = 1024; // Example resource limit

int registersPerThread = 32;

int sharedMemoryPerBlock = 1024; // bytes

// Choose block size to maximize occupancy while respecting limits

int threadsPerBlock = 256; // Multiple of warp size (32)

int numberOfBlocks = (N + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

divergentKernel<<<numberOfBlocks, threadsPerBlock>>>(d_data, N);

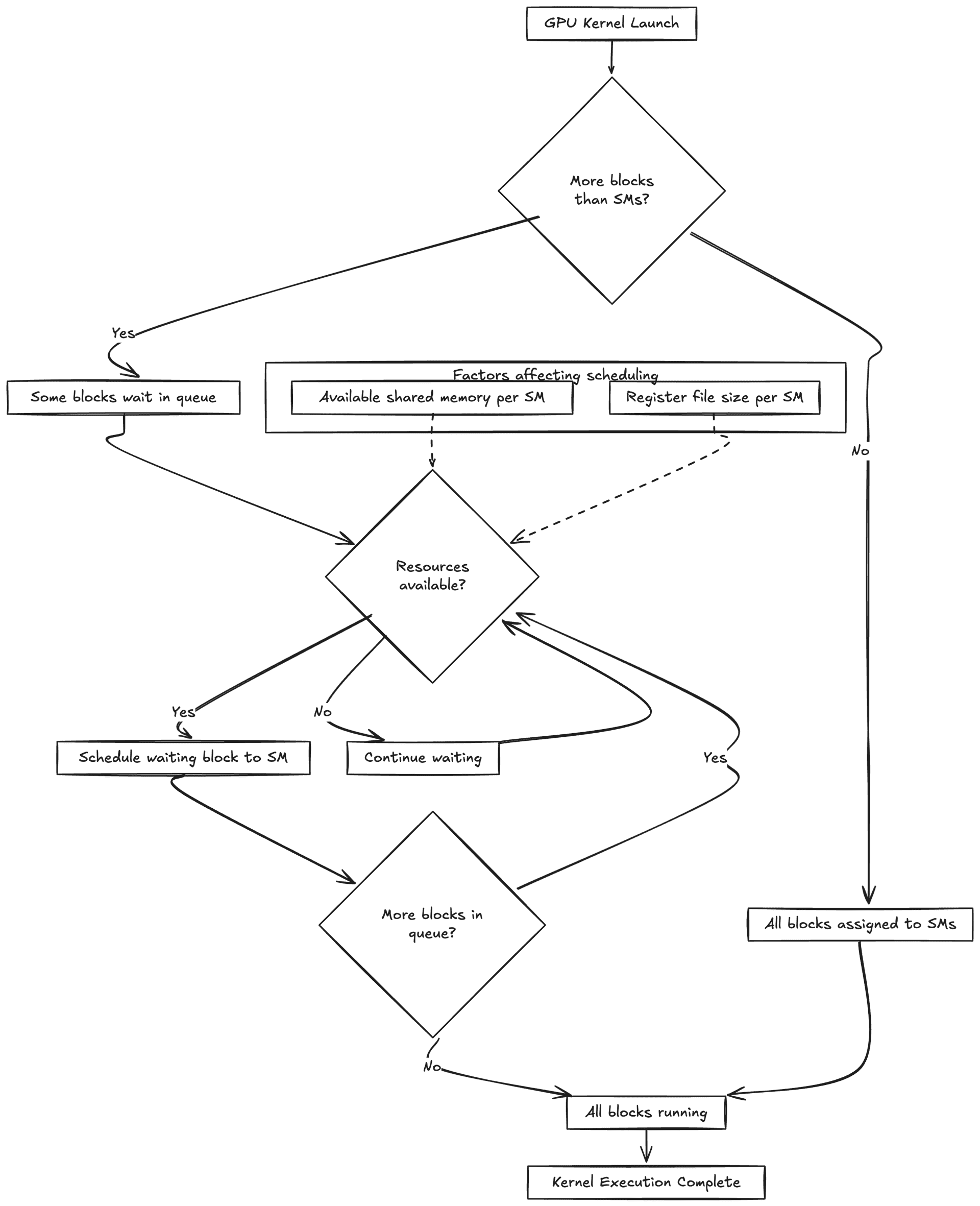

The GPU's scheduler manages blocks across available SMs. If there are more blocks than SMs, blocks wait in a queue and are scheduled as resources become available. This scheduling depends on factors like available shared memory and register file size per SM, which limit how many blocks can run concurrently.

In practice, choosing the wrong block size can tank performance. Getting it right means balancing parallelism against resource usage on each SM.

Quiz

What role does the thread block size play in CUDA kernel performance?

Thread Blocks and Grids

Now that threads are organized into warps (32 threads each), grouped into blocks, and scheduled onto Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs), let's zoom out.

A thread block is a group of threads that cooperate via shared memory and synchronization, all running on the same SM. Think of a block as a team of threads working together on a portion of the data. The grid is all the blocks launched by a kernel—every team tackling the entire problem. The diagram below shows how the grid breaks into blocks, blocks into warps, and warps into threads.

One reason for blocks is purely practical: there's a hardware limit on how many threads one can launch in a single block (typically 1024 threads maximum in current GPUs). If the problem needs more threads than that, one must split them into multiple blocks. For example, suppose you want to add two arrays of 2048 elements. You can use 2 blocks of 1024 threads each, block 0 handles indices 0–1023 and block 1 handles indices 1024–2047. In general, if you have N elements and your block can have at most B threads, you'd launch ceil(N/B) blocks so that all elements get covered. In the earlier vector addition example, we launched 3907 blocks of 256 threads to handle 1,000,000 elements. The collection of all these blocks (3907 of them) is the grid.

Another reason for blocks is that they allow scaling and scheduling flexibility. The GPU has a certain number of SMs (say your GPU has 20 SMs). Each SM can run a few blocks at a time, depending on resource availability. If 100 blocks are launched and only 20 can run concurrently (one per SM), the GPU starts 20 blocks in parallel and schedules the next block on a free SM as soon as one finishes.

Collectively, those 100 blocks produce the result as if 100 × blockSize threads ran at once. The runtime distributes them across hardware. A workload can exceed the number of threads the GPU can physically run simultaneously—the scheduler just time-slices blocks as needed. Blocks also let you control how much work runs in parallel, which matters when you're constrained on shared memory or registers.

Threads within a block can share a fast, on-chip memory space and synchronize using barriers. This is what makes intra-block cooperation practical. But it only works within a block—threads in different blocks have to go through slower global memory and can't directly synchronize with each other. That constraint is deliberate: it lets the scheduler place blocks on any SM without worrying about cross-block dependencies, so CUDA programs scale across GPUs with different numbers of SMs.

In practice, people use powers of 2 for threads per block (128, 256, or 512) to align with the warp size of 32. The choice matters more than you'd expect—it affects how well the GPU can hide memory latency by swapping between warps while others wait on data.

Here's a simple example that demonstrates how blocks and grids work together to process a large array:

__global__ void processLargeArray(float* input, float* output, int N) {

// Calculate global thread index from block and thread indices

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// Guard against out-of-bounds access

if (idx < N) {

// Each thread processes one element

// For this example, just multiply each element by 2

output[idx] = input[idx] * 2.0f;

}

}

// Host code to launch the kernel

void launchProcessing(float* d_input, float* d_output, int N) {

// Choose number of threads per block (power of 2, <= 1024)

const int threadsPerBlock = 256;

// Calculate number of blocks needed to process N elements

int numBlocks = (N + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

// Launch kernel with calculated grid dimensions

processLargeArray<<<numBlocks, threadsPerBlock>>>(d_input, d_output, N);

}

Notice how the kernel uses blockIdx.x, blockDim.x, and threadIdx.x to calculate a unique global index for each thread. The host code checks array bounds because the number of threads may be rounded up to the next block size, and it calculates the required number of blocks using ceiling division. Each thread processes exactly one element—a clean one-to-one mapping between threads and data.

Quiz

Why can't we launch a single block with 10,000 threads to handle 10,000 tasks on the GPU?

Memory Management in CUDA

In CUDA, you manage data movement between CPU (host) and GPU (device) yourself. The CPU and GPU have separate memory spaces: RAM for the CPU, VRAM for the GPU. You can't access one from the other directly—data has to be copied across the PCIe (or NVLink) bus. If you're coming from PyTorch, where moving a tensor to the GPU is one line, this feels like a lot of ceremony.

In raw CUDA C/C++, a common pattern is: allocate memory on the GPU (cudaMalloc), copy data from host to device (cudaMemcpy), launch kernels to do computation, copy results back to host, and finally free GPU memory (cudaFree).

For example, to use vecAddKernel from before, here's what the code looks like:

int N = 1000000;

size_t bytes = N * sizeof(float);

// Allocate host memory and initialize

float *h_A = (float*)malloc(bytes);

float *h_B = (float*)malloc(bytes);

float *h_C = (float*)malloc(bytes);

// ... fill h_A and h_B with data ...

// Allocate device memory

float *d_A, *d_B, *d_C;

cudaMalloc(&d_A, bytes);

cudaMalloc(&d_B, bytes);

cudaMalloc(&d_C, bytes);

// Copy input arrays from host to device

cudaMemcpy(d_A, h_A, bytes, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(d_B, h_B, bytes, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// Launch kernel (using, say, 256 threads per block as before)

int threads = 256;

int blocks = (N + threads - 1) / threads;

vecAddKernel<<<blocks, threads>>>(d_A, d_B, d_C, N);

// Copy result array back to host

cudaMemcpy(h_C, d_C, bytes, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// Free device memory

cudaFree(d_A);

cudaFree(d_B);

cudaFree(d_C);

Quiz

What is the correct sequence of CUDA memory operations when working with GPU data?

Shared Memory and Synchronization

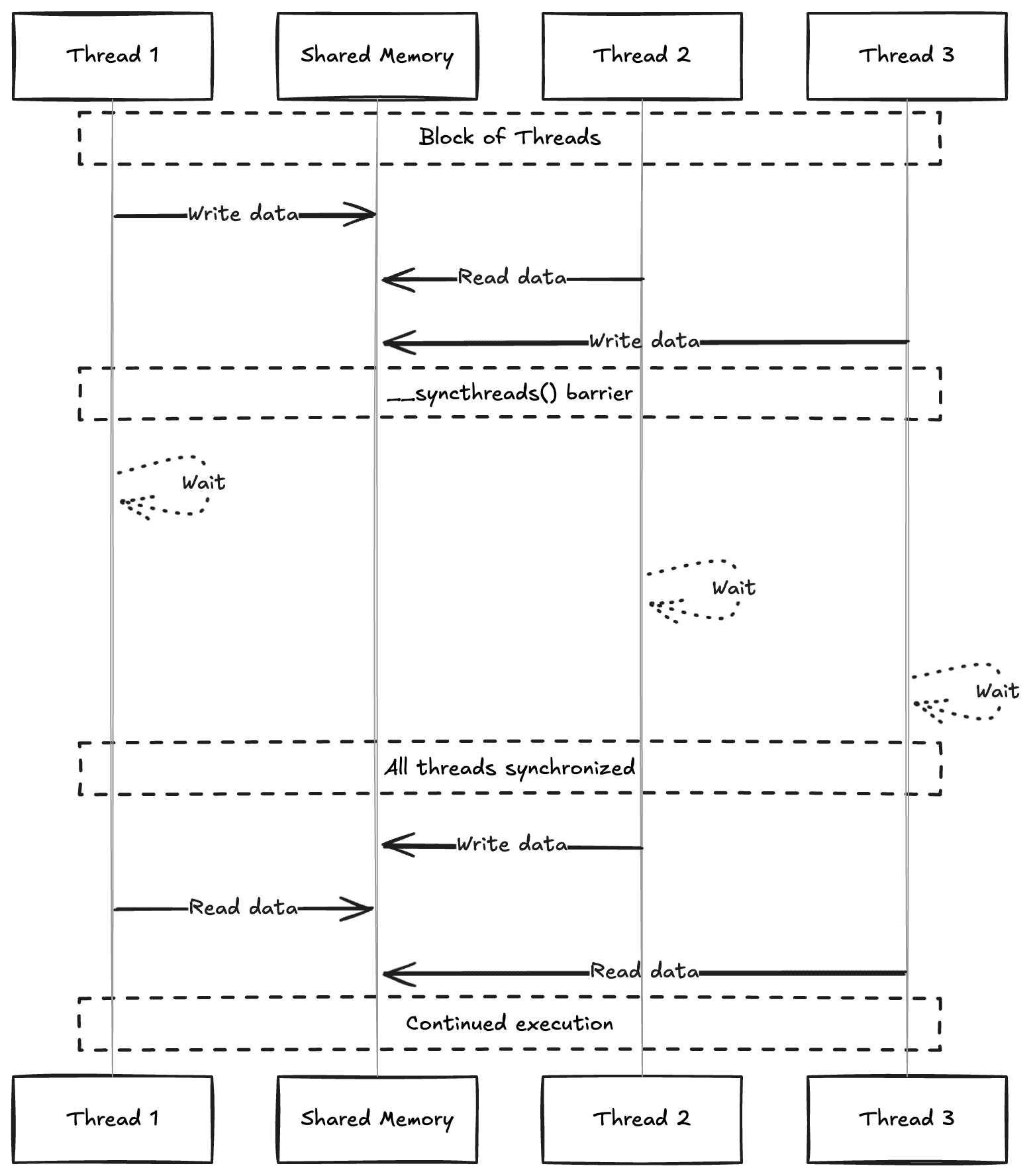

CUDA gives you access to shared memory, a fast on-chip memory that all threads in a block can read and write.

To coordinate access, you use __syncthreads() (or cuda.syncthreads() in Numba), which acts as a barrier—every thread in the block waits until all threads reach that point before any of them continue. Same idea as locks or barriers in Python multi-threading, but at the GPU level.

Here's an example:

__global__ void incrementElements(float *data, int n) {

__shared__ float tile[256]; // declare shared memory array

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int tid = threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

// Load element from global memory to shared memory

tile[tid] = data[idx];

__syncthreads(); // ensure all loads complete

// Each thread increments its element in shared memory

tile[tid] += 1.0f;

__syncthreads(); // ensure all threads finished updating

// Write the result back to global memory

data[idx] = tile[tid];

}

}

Quiz

What is the primary purpose of shared memory in CUDA programming?

Fused CUDA Kernels for LLMs

LLM workloads pushed people to write custom CUDA kernels that fuse multiple operations into one, cutting down on memory traffic [1, 1]. The most well-known example is FlashAttention [1], which speeds up Transformer self-attention by reducing memory reads and writes.

Standard Transformer self-attention is:

where , , and are the query, key, and value matrices, and is the dimension of the key vectors.

FlashAttention tiles this computation in GPU shared memory so that data gets read from and written to global memory far fewer times. The speedup is especially noticeable for long sequences.

Understanding how CUDA kernels work at this level has helped me write custom fused kernels that beat naive PyTorch implementations.

FlashAttention: PyTorch vs CUDA Implementation

PyTorch Implementation

import torch, math

def flash_attention_pytorch(Q, K, V, block_size=16):

"""

Compute attention scores with memory-efficient block-wise operations.

Args:

Q: Query matrix [N_out x d]

K: Key matrix [N_inp x d]

V: Value matrix [N_inp x d]

block_size: Size of blocks for tiled computation

Returns:

O: Output matrix [N_out x d]

"""

N_out, d = Q.shape

N_inp = K.shape[0]

# Initialize output tensors

O = torch.zeros(N_out, d, device=Q.device)

L = torch.zeros(N_out, 1, device=Q.device)

# Calculate number of blocks needed

T_c = (N_inp + block_size - 1) // block_size # Ceiling division

T_r = (N_out + block_size - 1) // block_size

scale_factor = 1 / math.sqrt(d)

# Process Q and O in T_r blocks; K, V in T_c blocks

for i in range(T_r):

# Get current block of queries

q_start = i * block_size

q_end = min((i + 1) * block_size, N_out)

Q_block = Q[q_start:q_end]

# Initialize block accumulators

O_block = torch.zeros(q_end - q_start, d, device=Q.device)

L_block = torch.zeros(q_end - q_start, 1, device=Q.device)

m_block = torch.full((q_end - q_start, 1), float('-inf'), device=Q.device)

last_m = m_block.clone()

# Process K,V in blocks

for j in range(T_c):

k_start = j * block_size

k_end = min((j + 1) * block_size, N_inp)

K_block = K[k_start:k_end]

V_block = V[k_start:k_end]

# Compute attention scores for this block

S_block = scale_factor * (Q_block @ K_block.T) # [B_r x B_c]

# Update running maximum for numerical stability

m_block = torch.maximum(m_block, S_block.max(dim=-1, keepdim=True).values)

# Compute attention weights with numerical stability

P_block = torch.exp(S_block - m_block) # [B_r x B_c]

# Update accumulators with scaling factor from updated maximum

scaling_factor = torch.exp(last_m - m_block)

L_block = scaling_factor * L_block + P_block.sum(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

O_block = scaling_factor * O_block + P_block @ V_block

last_m = m_block.clone()

# Store results for this block

O[q_start:q_end] = O_block / L_block # Normalize with accumulated sum

L[q_start:q_end] = L_block

return O

The key ideas: process matrices in blocks so you don't need the full attention matrix in memory at once, use the max-trick for numerical stability in softmax, and keep a running maximum (last_m) to rescale previous computations when a new max appears. Results accumulate block by block, so long sequences don't blow up memory.

CUDA Implementation

Here's the equivalent CUDA kernel that fuses these operations:

constexpr int BLOCK_SIZE = 16;

constexpr int HIDDEN_DIM = 128;

extern "C" __global__ void flash_attention_cuda(

float* output, // [N_out x d]

float* output_lse, // [N_out]

const float* query, // [N_out x d]

const float* key, // [N_inp x d]

const float* value, // [N_inp x d]

const float scale,

const int N_out,

const int N_inp) {

// Shared memory for block-wise computation

__shared__ float q_block[BLOCK_SIZE][HIDDEN_DIM];

__shared__ float k_block[BLOCK_SIZE][HIDDEN_DIM];

__shared__ float v_block[BLOCK_SIZE][HIDDEN_DIM];

// Thread indices

const int tx = threadIdx.x;

const int ty = threadIdx.y;

const int row = blockIdx.x * BLOCK_SIZE + tx;

// Local accumulators in registers

float m_i = -INFINITY;

float l_i = 0.0f;

float o_i[HIDDEN_DIM] = {0.0f};

// Process input in tiles

for (int tile = 0; tile < (N_inp + BLOCK_SIZE - 1) / BLOCK_SIZE; ++tile) {

// Load query block (done once per outer loop)

if (tile == 0 && row < N_out) {

for (int d = 0; d < HIDDEN_DIM; d += blockDim.y) {

int d_idx = d + ty;

if (d_idx < HIDDEN_DIM) {

q_block[tx][d_idx] = query[row * HIDDEN_DIM + d_idx];

}

}

}

__syncthreads();

// Load key and value blocks

if (tile * BLOCK_SIZE + ty < N_inp && row < N_out) {

for (int d = 0; d < HIDDEN_DIM; d += blockDim.y) {

int d_idx = d + ty;

if (d_idx < HIDDEN_DIM) {

k_block[tx][d_idx] = key[(tile * BLOCK_SIZE + tx) * HIDDEN_DIM + d_idx];

v_block[tx][d_idx] = value[(tile * BLOCK_SIZE + tx) * HIDDEN_DIM + d_idx];

}

}

}

__syncthreads();

// Compute attention scores and update accumulators

if (row < N_out) {

float m_prev = m_i;

// Compute scores and find max for stability

float max_score = -INFINITY;

float scores[BLOCK_SIZE];

#pragma unroll

for (int j = 0; j < BLOCK_SIZE && tile * BLOCK_SIZE + j < N_inp; ++j) {

float score = 0.0f;

#pragma unroll

for (int d = 0; d < HIDDEN_DIM; ++d) {

score += q_block[tx][d] * k_block[j][d];

}

scores[j] = scale * score;

max_score = max(max_score, scores[j]);

}

// Update running max and scale previous results

m_i = max(m_i, max_score);

float scale_factor = exp(m_prev - m_i);

l_i *= scale_factor;

#pragma unroll

for (int d = 0; d < HIDDEN_DIM; ++d) {

o_i[d] *= scale_factor;

}

// Compute attention and update output

#pragma unroll

for (int j = 0; j < BLOCK_SIZE && tile * BLOCK_SIZE + j < N_inp; ++j) {

float p_ij = exp(scores[j] - m_i);

l_i += p_ij;

#pragma unroll

for (int d = 0; d < HIDDEN_DIM; ++d) {

o_i[d] += p_ij * v_block[j][d];

}

}

}

__syncthreads();

}

// Write final output

if (row < N_out) {

float inv_l = 1.0f / l_i;

for (int d = 0; d < HIDDEN_DIM; ++d) {

output[row * HIDDEN_DIM + d] = o_i[d] * inv_l;

}

output_lse[row] = l_i;

}

}

Why is the CUDA version faster? __shared__ memory replaces repeated slicing from global memory. Accumulators live in registers instead of tensor allocations. Rows get processed in parallel across threads rather than sequentially. The structured memory loads coalesce into fewer transactions, and #pragma unroll eliminates loop overhead that PyTorch's interpreter can't.